The floor of Jen Grady’s classroom at Mattie Washburn Elementary School was shaking ever so slightly.

On the plush grid of her multicolored carpet, 10 pairs of feet landed with muffled, rhythmic thuds. As the students, all first-graders, hopped, they sounded out the letter “r,” a tricky consonant for many 6- and 7-year-olds to master. But the movement, mimicking a rabbit, held a clue, Grady reminded them. “It’s a developmental thing,” she explains. “They want to say, ‘er.’”

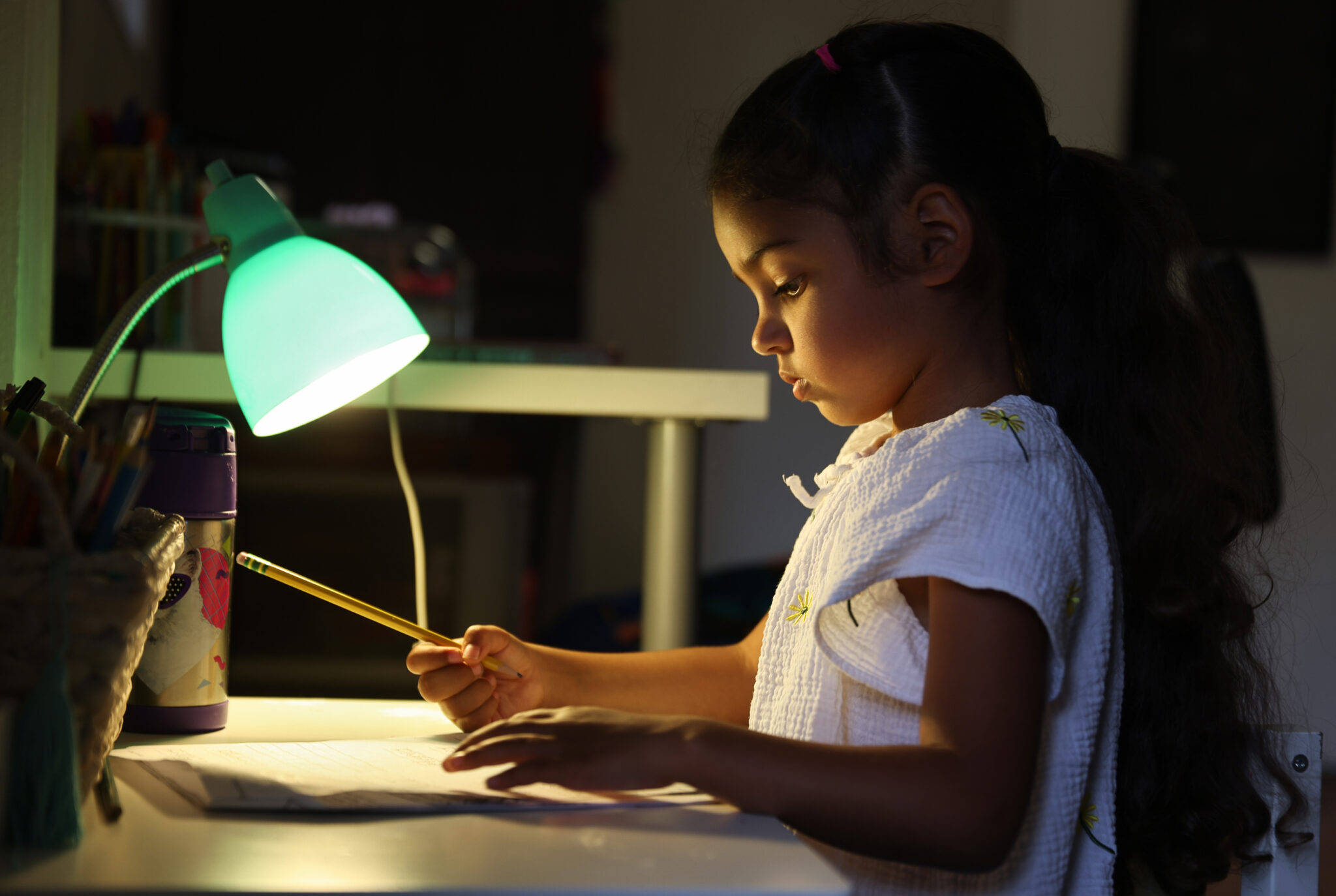

As a reading intervention specialist who has spent 19 years at the K-2 campus in Windsor, Grady’s job is to help students struggling to meet California’s grade level standards in reading and writing. This academic year, that work — and the shared experience for many fellow teachers across Sonoma County — has been an unsettling game of catch-up. “We struggled choosing who was going to get the spots” in her classroom, Grady says. “Because so many of them needed it. Because so many of them are behind.”

The return of nearly all of Sonoma’s 66,450 public school students to classrooms in August was hailed as a pandemic milestone. As a group, they had been stuck at home and consigned mostly to online-based instruction since March 2020, in some cases for months longer than most of their Bay Area peers—the result of stubbornly high local Covid case rates and local public health guidelines that were among the most conservative in the state.

Continue Reading on Sonoma Magazine